In March 2019, after decades of construction, Hudson Yards welcomed the public into its plazas and towers for the first time. Built atop a carefully engineered deck that disguises thirty active Long Island Rail Road train tracks, the current development includes four skyscrapers, a mall, and an arts center called The Shed. On those first spring days, visitors flowed out from a shiny 7 train station, through a series of mid-block green spaces called Bella Abzug Park, and into a public plaza featuring a massive, climbable structure known as the Vessel. Manhattan’s newest destination, seeming both novel and inevitable, had arrived.

Almost immediately upon opening, critics lambasted the mega-development as nothing more than the city’s newest tourist trap and a playground for the ultra-wealthy; due to its imposing scale, price tag of $25 billion, and lack of affordable housing and retail. New York Times architecture writer Michael Kimmelman deemed the project a “vast neoliberal Zion… [that] glorifies a kind of surface spectacle — as if the peak ambitions of city life were consuming luxury goods,”1 while Citylab reporter Feargus O’Sullivan called the Vessel and surrounding shops an “Instagram-friendly panopticon.”2

Other criticisms focused on the fiscal aspects of Hudson Yards. A report from The New School tracked the numerous public subsidies given to Related, the project’s developer, including everything from the cost of the 7 subway extension to discounts and deferrals on income taxes and interest payments.3 Additionally, writer Kriston Capps reported on state documents which revealed that Related raised at least $1.2 billion for the development through the EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program, using “a form of creative financial gerrymandering” to divert funds from lower-income neighborhoods.4 These reports point to a larger central criticism of Hudson Yards: that it exists, fundamentally and inevitably, outside of the true New York City, less like a new neighborhood and more of a gated community.5 This sense of place comprises the current urban imaginary of Hudson Yards, which takes root not in the architectural details or funding structures of the project, but in the political framings and causal stories set out in the planning documents that defined the discourse surrounding the Far West Side in the early and mid-2000s. The local community activism and production of competing plans in Hell’s Kitchen shaped the scale of the area’s urban imaginary long before Related signed on as a developer. As David Smiley, a professor of urban design at Columbia University, eloquently put it: “once the buildings go up, you’re too late.”6

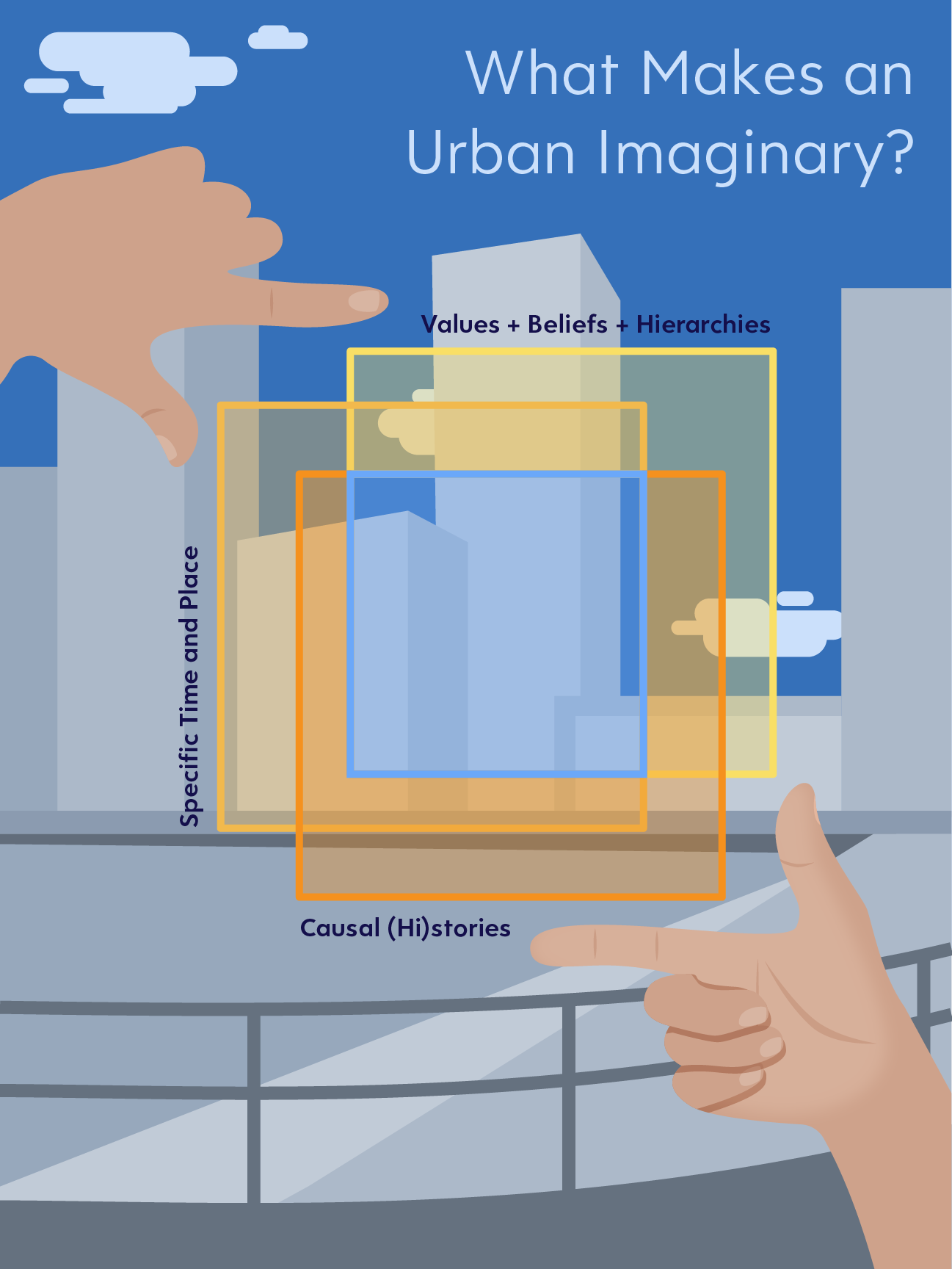

While urban plans influence the physical aspects of a neighborhood through tools like zoning ordinances and street design, their language also shapes the local urban imaginary, working to shift the sociocultural perceptions of a place to align with a policymaker’s specific set of priorities. The relational “set of meanings about cities that arise in a specific historical time and cultural space” comprise an area’s urban imaginary, constantly shifting with the passage of time.7 The evolution of public discourse and sociocultural understandings of Coney Island exemplify these changes. In the early 1900s, Coney Island’s amusement parks and beaches were extremely popular, welcoming massive numbers of residents and tourists across class divides. As decades passed and interest in these amusements waned, planners like Robert Moses explicitly recast Coney Island as a lower-class, “blighted,” and “dependent” place, mirroring a broader shift in the cultural scope of the American Dream (from public assistance to private bootstrapping). This converged with racialized depictions of Southern Brooklyn, as Black and Latino populations increased, planners’ and politicians’ descriptions of the area’s blight intensified.8 This Coney Island example reveals that urban imaginaries extend beyond sheer cultural stereotypes, and as such they can be both “deliberately orchestrated” and “accumulated by degrees” at various points in time.9

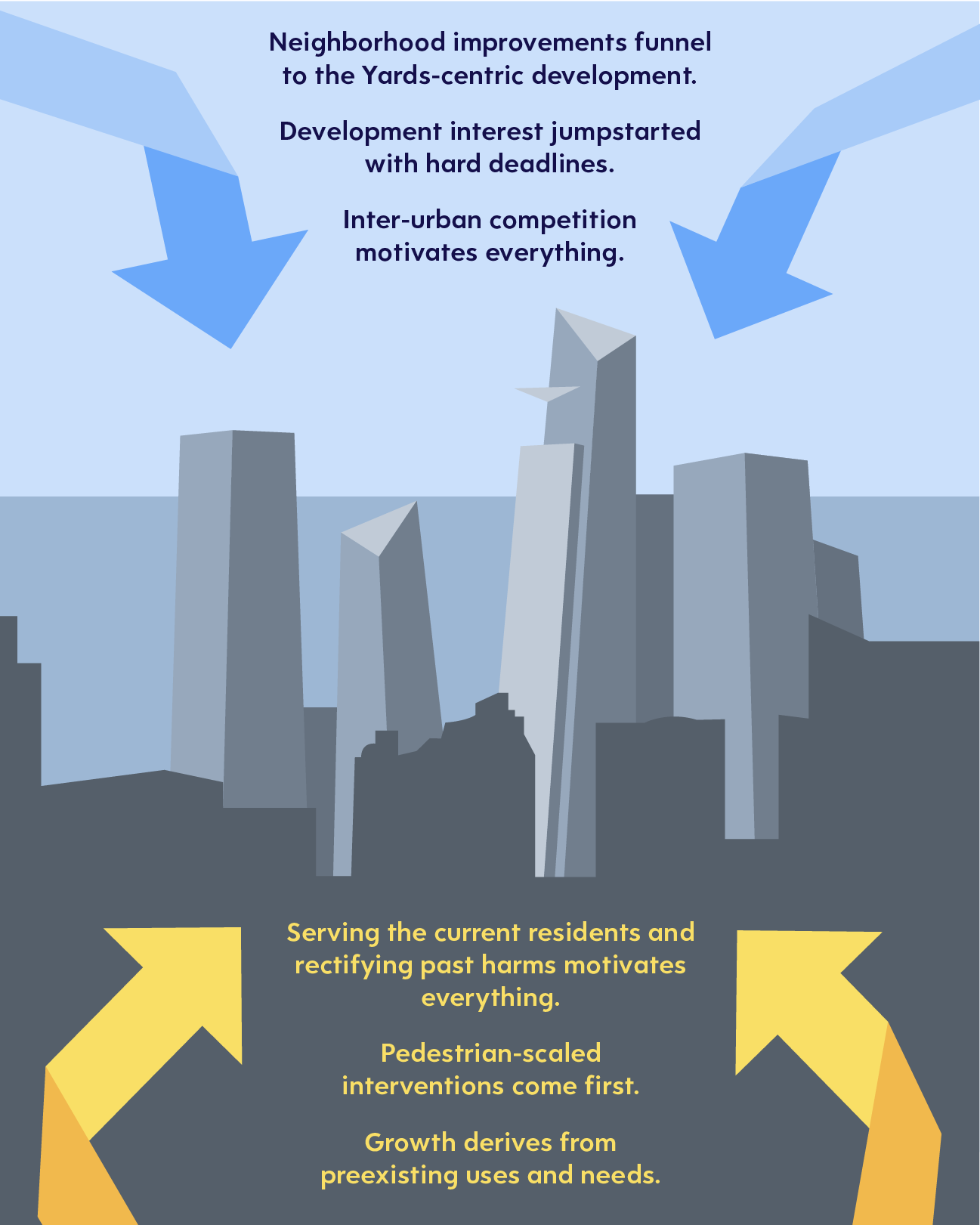

Urban imaginaries also imply a set of causal stories about a place’s origins, current population, and future needs. Like these stories, urban imaginaries can help “move situations intellectually from the realm of fate to the realm of human agency” by outlining which issues need intervention in the public realm.10 Most importantly, urban imaginaries dictate the scale and scope of necessary interventions, contributing to the process of image making that both creates and upholds problem definitions. This scale of the urban imaginary became the site of struggle for planning elites and neighborhood residents on the Far West Side as both groups sought to control the future growth of the neighborhood. Although many of the early plans for Hell’s Kitchen shared similar requirements for zoning and green space, city officials and private stakeholders crafted plans that located Hudson Yards as a flagship site of commercial inter-urban competition, while local community members recast the development as one key element in a broader framework for neighborhood growth and change. Ultimately, the residual tension between these contrasting visions produces the sense of Hudson Yards (as an unfinished quasi-neighborhood) that New Yorkers know today.

The Far West Side, Hell’s Kitchen, and Hudson Yards: Community Documentation

Tracing the history of these shifting urban imaginaries requires establishing a baseline understanding of the geography and demographic makeup of the area surrounding Hudson Yards, since the East and West Rail Yards on which Related’s skyscrapers sit comprise only one small portion of the larger Hell’s Kitchen district. In most of the large-scale neighborhood plans, the Far West Side extends from 8th Avenue to the Hudson River, bounded by 42nd street to the north and 28th street to the south. As many of these planning documents note, a mix of low-rise residential buildings, converted lofts, manufacturing facilities, and transit infrastructure populate the area. This variation can create starkly different experiences from block to block, as pedestrians turn away from the shops and walk-up apartments on 9th Avenue only to be confronted by the “spaghetti” of disjointed crosswalks and roadways feeding into the Lincoln Tunnel.11 This unique spatial configuration inspired creative interventions in many of the plans drafted for the area.

As with any New York City neighborhood, the population of Hell’s Kitchen has followed long-term trends in demographic change. Puerto Rican and European immigrants were the primary residents of the area for much of the 20th Century, populations which slowly decreased amidst initial waves of gentrification. According to data from the U.S. Census and American Community Survey, the population grew gradually in the early 2000s, then spiked in the late 2010s (likely as a result of new residential development). The number of Black and Hispanic residents remained largely stable from 2000 to 2020 as local white and Asian populations grew around them, resulting in lower population proportions as shown below.12

| 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 14,613 | 19,727 | 31,426 |

| Median Household Income | $41,242 ($71,741 in 2022) | $71,610 ($95,543 in 2022) | $104,444 |

| Employment | 68.2% of residents had at least some college education, 87.5% employment rate | Majority of workers in management, sales, or other white-collar work | Workers even more concentrated in white-collar professions |

| Racial Demographics | 50.4% white, 22.7% Hispanic/Latino, 12.9% Black, 10.4% Asian, 3.6% other categories | 53% white, 14% Black, 14% Asian, 17% Hispanic/Latino, 5% other categories | 51% white, 14% Hispanic, 25% Asian, 5% Black, 5% other categories |

Over the past few decades, Hell’s Kitchen has become a haven for businesspeople, artists, and other highly educated and well-resourced professionals. Longtime resident and architect Meta Brunzema described the area in the late 1990s as a “mixed community” of small business owners, Broadway performers, midtown office workers, and creatives across disciplines. She remarked that “loft-living artists” and freelancers organized the local block associations and neighborhood groups that sought to shape planning priorities in the ensuing years.13 These demographic profiles depict a community with access to financial resources and technical expertise (especially in planning and design-related fields) as well as flexible time to organize, making them uniquely poised to exert political agency in the early development of Hudson Yards.

Laying the Groundwork

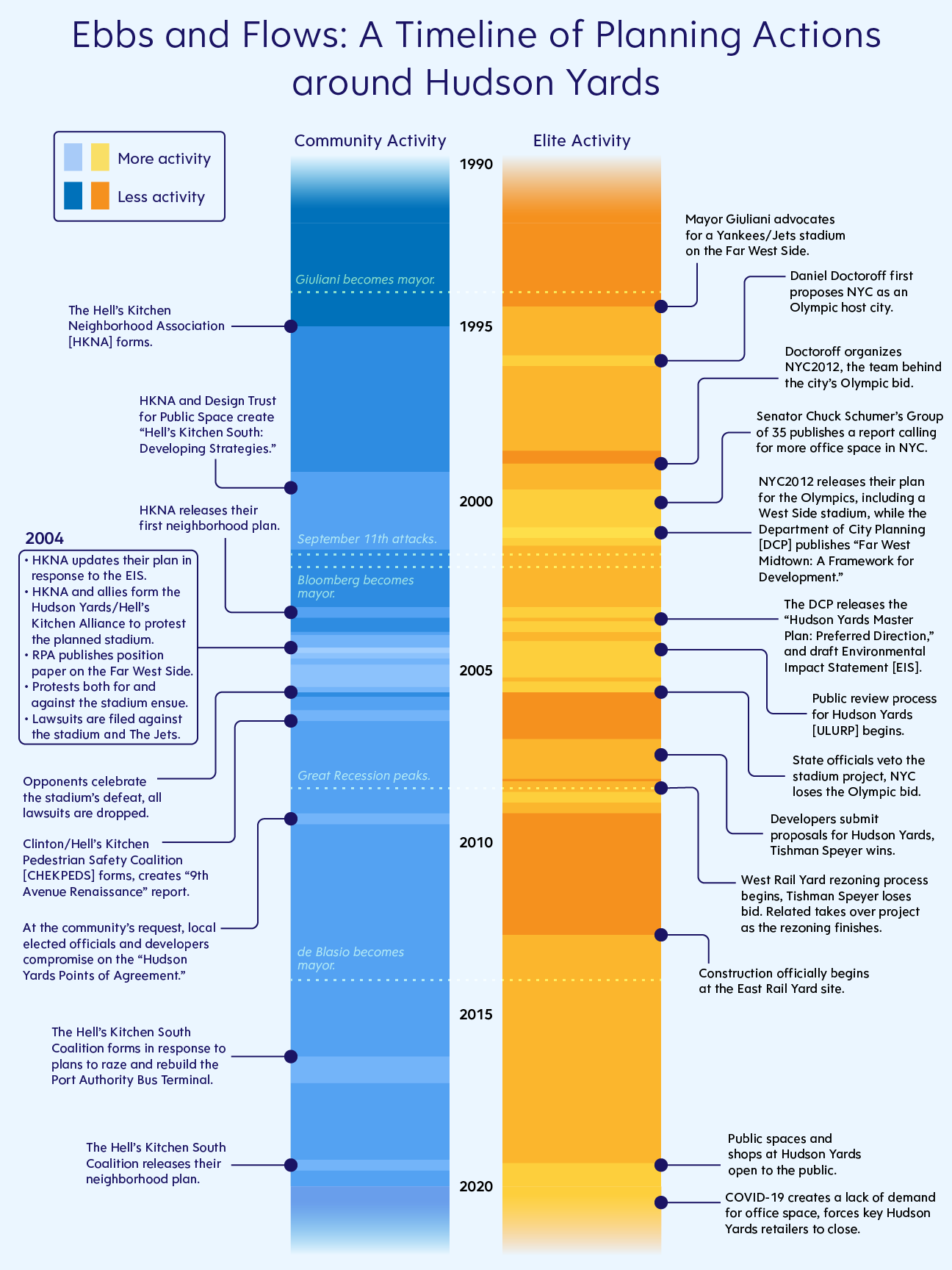

The history of planning actions around Hudson Yards begins well before the start of this timeline. In the late 1970s, former head of the MTA Richard Ravitch “oversaw the construction of support columns in the yards that would be able to support a deck,” immediately spurring private interest in the newly profitable space just west of the midtown core.14 A variety of proposals for the site fell through, including a stadium for the Yankees envisioned by former Mayor Giuliani. Despite the flurry of speculation, the urban imaginary had yet to coalesce around Hudson Yards, guiding the vision for its purpose. This changed in 1995, when investment banker Daniel Doctoroff began organizing planners, developers, and power brokers to build New York City’s bid for host city of the 2012 Olympics. At once “an efficient planning solution, an audacious mega-project proposal, and an intricate political balancing act,” the Olympic planning team, known as NYC2012, provided public officials with a “patina of legitimacy” for a previously inconceivable scale of redevelopment at various sites across the city.15

As Doctoroff and his team drafted their cross-borough site plan for the Games, Senator Chuck Schumer convened the Group of 35, a committee of local business leaders, to determine the state of the city’s economic needs moving into the new century. Their final report, published in 2001 just before the release of the NYC2012 plan, asserted that the city was running out of prime office space and could “miss out on hundreds of thousands of new jobs and increased economic activity” without new construction. The report called on the public sector to facilitate the new commercial development through the creation of expanded central business districts across the city, upholding the Far West Side as an example of a prime location for investment.16 At the same time, the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) published “Far West Midtown: A Framework for Development,” one of the most influential documents in the creation of Hudson Yards. In the Framework, the DCP laid out a master plan for the entire Hell’s Kitchen area, setting up boundaries and assumptions about necessary space and zoning followed by every subsequent city plan. It echoed the demands for office space expansion and subway extension from the NYC2012 and Group of 35 reports. Notably, the Framework’s language paints an image of the Far West Side as empty and devoid of character, a “transitional area without a strongly defined urban character or open space of any significance… that for decades has been seen only as a way for moving cars and buses in and out of the City – as a place you pass through on the way to somewhere else.”17 These three documents establish a clear urban imaginary of the Far West Side, portraying the area as a perfect blank slate on which to stage necessary feats of inter-urban commercial and cultural competition. Little did their authors realize that the residents of Hell’s Kitchen were at the same time busy crafting imaginaries of their own.

Around the same time that Daniel Doctoroff began gathering support for a New York Olympic bid, residents of the Far West Side formed community groups to improve the quality of life in their neighborhood. One such group, the Hell’s Kitchen Neighborhood Association (HKNA), constructed several small parks and public artworks suffused throughout the network of transit infrastructure that fragmented the area. By 1999, HKNA members felt that “development pressure in Hell’s Kitchen South [had] become acute,” and worked with a team of urban planners at the Design Trust for Public Space to develop their own vision for the neighborhood’s growth, with two years of local outreach and research culminating in a report titled “Hell’s Kitchen South: Developing Strategies.”18 The report’s authors sought to “maximize opportunities for positive change rather than prevent urban growth,” while also asserting that “Hell’s Kitchen South does not need to be cleaned-up, filled-in, covered-over or replaced.”19 To that end, the report’s various design proposals recommended augmenting open-air rail tracks with green space, encouraging the expansion of office buildings and the Javits Center without encroaching on waterfront access, and avoiding developments with “opaque street-level walls” in favor of “pedestrian amenities and commercial activity to enhance the street life of the neighborhood.”20 Intended as the first step in a multi-stage planning process, the authors of “Developing Strategies” suggested that residents “plan proactively, not reactively” and clearly define vague and often misinterpreted terms like “mixed-use” to their benefit.21 Unfortunately, the fixed timeline of the Olympic bid allowed elite stakeholders like Daniel Doctoroff (recently instated as Deputy Mayor for Economic Development and Rebuilding) to jumpstart public land use review for the area, putting HKNA on the defensive in the face of a burgeoning rezoning.

Round Two: The Public Arena

In 2003, the Department of City Planning released the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the Hudson Yards Uniform Land Use Review Process (ULURP), introducing the city’s preferred zoning and design designations for the Far West Side. The EIS checked every political box, allowing for the construction of supertall office towers, an expansion of the Javits Center, midblock green spaces and public plazas, and a New York Sports and Convention Center (and adjacent parking lot) to be filled with Olympics spectators or New York Jets fans. Much to the chagrin of the Hell’s Kitchen Neighborhood Association, the EIS’ authors justified the addition of a stadium through familiar buzzwords: “Large areas of underutilized urban landscape would be replaced with the dense, new, active and lively 24-hour mixed-use Hudson Yards community.”22

In response, HKNA members drafted their own plan, to be included as an alternative to the city’s preferred direction in the final EIS. This document extended the concepts from “Developing Strategies” into actionable steps, but ultimately took a reactionary stance to many of the DCP’s proposed changes to the area. HKNA’s plan proposed lower-scale commercial zoning along the neighborhood’s Western edge to keep the waterfront more open and inviting. In contrast to the EIS, which made allusions to preserving housing affordability but no explicit changes, the plan increased the proportion of housing in areas with new development (paired with an innovative affordability mandate). Most importantly, they eschewed the stadium in favor of a low-rise Javits Center expansion topped with a park, legitimizing their plan by claiming that they were “able to plan an expansion of the Javits Center today only because of the foresight of the Legislature and the local community.”23 Although the DCP dismissed the HKNA alternative as not economically viable, this community-led plan existed as a valuable form of socio-cultural mapping, creating a contrasting view of the Far West Side that informed public perceptions of the development throughout the 2000s.24 Instead of taking a top-down, inter-urban view of the Far West Side’s urban imaginary, members of HKNA saw their neighborhood from the ground up, as a place where development and growth could support existing residents, unify a physically fragmented area, and improve the quality of life for anyone in the neighborhood.

Crisis Averted?

In 2005, HKNA joined with local faith communities, other block associations, and shop owners to form the Hudson Yards/Hell’s Kitchen Alliance, a coalition with the express goal of stopping any plan for a stadium on the Far West Side. Prestigious institutions of urban planning like the Regional Plan Association and the Municipal Arts Society supported the Alliance’s demands for local development without the stadium, arguing that “removing the most controversial element of the plan [the stadium] may actually enhance the likelihood that the rest of the plan will be implemented.”25 The RPA’s position received a scathing critique from then-Deputy Mayor Doctoroff, who invoked the pressures of impending investment and the Olympic deadline to reinforce the city’s goal of inter-urban competition:

“A critical issue is timing. Given the expected gradual pace of development, it is important to fill the area with exciting uses today, or else face even slower progress. The Jets are ready to invest now to fill in the gaping hole that is the Western Rail Yard. Once the Jets have anchored the western edge of the Hudson Yards, the development of the Eastern Rail Yard and the 11th Avenue corridor will be proceed more quickly.”26

Amidst these waves of protest and open rebukes, the Public Authorities Control Board vetoed the plan for the stadium in June of 2005, and by July, New York City had officially lost the bid for Olympic host city. In the wake of their victory over the stadium, the Hudson Yards/Hell’s Kitchen Alliance dissolved, the Hell’s Kitchen Neighborhood Association continued with smaller-scale improvements to the district, and new community groups like the Clinton/Hell’s Kitchen Pedestrian Safety Coalition (CHEKPEDS) spun off from HKNA to combat the neighborhood’s perennial lack of green space and pedestrian-friendly roadways. Despite their losses, the city was “not prepared to waste the opportunity of using an Olympic bid as a catalyst to drive the city forward,” inviting developers to submit bids to deck over and build atop the newly rezoned East Rail Yard.27 Within three years, the DCP rezoned the West Rail Yard for inclusion in the project to far less fanfare and opposition. By the time Related broke ground on the site, the contest for the future of Hudson Yards was fast fading into the realm of memory, but the competing urban imaginaries forged in the struggle remained.

In the years following the defeat of the planned stadium, neither urban imaginary truly won out over the other. The Far West Side never achieved the degree of global prestige or competitiveness that the Olympics offered, nor did the DCP’s approved zoning ensure that the Hudson Yards development would integrate with the surrounding neighborhood. Indeed, Bella Abzug Park, the city’s proposed mid-block boulevard, sits half-finished and interrupted by rows of parked cars. The windowless eastern facade of the Shops at Hudson Yards (now stripped of the Neiman Marcus name) juts out over 10th Avenue, the epitome of an “opaque street-level wall.”28

Despite over twenty years of planning, dealmaking, and activism at Hudson Yards, this tension between competing urban imaginaries only further isolates the development from the rest of the neighborhood while broader issues within Hell’s Kitchen remain unresolved. In 2015, local residents formed the Hell’s Kitchen South Coalition in response to the possible relocation of the Port Authority Bus Terminal. By 2019 they had crafted a neighborhood plan seeking to address many of the same problems articulated in HKNA’s “Developing Strategies,” with goals to “improve pedestrian safety… provide permanently affordable units in new buildings,” and “re-unify the bifurcated halves of the neighborhood with inter-connected parks.”29 Even a massive influx of private investment failed to address the challenges created by this harmful legacy of planning.

The complex history of Hudson Yards reveals that the language and framings deployed in planning documents can deeply affect the built environment of a neighborhood. This is only the latest example in a long history of linguistic justifications for planning interventions, from notions of so-called blight to environmental ideals of resilience and adaptation. The lasting urban imaginary of Hudson Yards still remains to be seen. For now, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the development exists primarily as a tourist attraction opposite an empty East Rail Yard, a storage space for the deferred hopes of the Far West Side.

About the Project

This article was researched, written and illustrated by Marc Ella Roy. All demographic statistics were collected from the US Census and American Community Survey using Social Explorer. This project would not have been possible without the input of Meta Brunzema, David Smiley, and Christine Berthet, who provided invaluable wisdom and context for the development of these plans. Gratitude also to Charles Komanoff for being a sounding board for my ideas. Lastly, a huge thank you to Prof. Laura Wolf-Powers. Your guidance and openness were invaluable- I am a better thinker, writer, and planner because of you.

Bibliography

1. Kimmelman, M. (2019, March 14). Hudson Yards is Manhattan’s biggest, newest, slickest gated community. Is this the neighborhood New York deserves? The New York Times. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/03/14/arts/design/hudson-yards-nyc.html

2. O’Sullivan, F. (2019, March 19). Cities Deserve Better Than These Thomas Heatherwick Gimmicks. Bloomberg Citylab. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-03-19/hudson-yards-s-vessel-more-gaudy-thomas-heatherwick.

3. Fisher, B., and Leite, F. (2018, November). The Cost of New York City’s Hudson Yards Redevelopment Project. Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis and Department of Economics, The New School for Social Research, Working Paper Series 2018-2.

4. Capps, K. (2019, April 12). The Hidden Horror of Hudson Yards Is How It Was Financed. Bloomberg CityLab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-04-12/the-visa-program-that-helped-pay-for-hudson-yards

5. Kimmelman, M. (2019).

6. Smiley, D. (2022, March 19). Personal Communication [Personal interview].

7. Zukin, Baskerville, R., Greenberg, M., Guthreau, C., Halley, J., Halling, M., Lawler, K., Nerio, R., Stack, R., Vitale, A., & Wissinger, B. (1998). From Coney Island to Las Vegas in the Urban Imaginary: Discursive Practices of Growth and Decline. Urban Affairs Review (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), 33(5), 627–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/107808749803300502

8. Zukin et. al. (1998).

9. Zukin et. al. (1998).

10. Stone, D. (1989). Causal Stories and the Formation of Policy Agendas. Political Science Quarterly, 104(2), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.2307/2151585

11. Conard, M., and Smiley, D. (2002). Hell’s Kitchen South: Developing Strategies. The Design Trust for Public Space. Fälth & Hassler.

12. SE:A00001-SE:A1007B (American Community Survey 2010 and 2020). In SocialExplorer.com. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.socialexplorer.com/b3e9bd399f/view

13. Brunzema, M. (2022, March 17). Personal Communication [Personal interview].

14. Brash, J. (2006, October). The Bloomberg Way: Development Politics, Urban Ideology, and Class Transformation in Contemporary New York City [Doctoral dissertation, CUNY Graduate Center]. CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1440/

15. Brash, J. (2006, October).

16. Samuelian, M. (2020, January 15). Where Did Hudson Yards Come From? This Little-Known Report Helped Start It All. Gotham Gazette. https://www.gothamgazette.com/opinion/130-opinion/9049-where-hudson-yards-come-from-little-known-schumer-report-helped-start-it-all

17. New York City Department of City Planning. (2001). Far West Midtown: A Framework for Development. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/plans/hudson-yards/fwmt.pdf

18. Conard, M., and Smiley, D. (2002). pg. 5.

19. Conard, M., and Smiley, D. (2002). pg. 7.

20. Conard, M., and Smiley, D. (2002). pg. 113.

21. Conard, M., and Smiley, D. (2002). pg. 102.

22. New York City Department of City Planning (August 2004). No. 7 Subway Extension—Hudson Yards Rezoning and Development Program: Final Generic Environmental Impact Statement Executive Summary. NYC DCP. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/about/publications.page.

23. Hell’s Kitchen Neighborhood Association (2004, November). HKNA’s Plan for the Hell’s Kitchen / Hudson Yards Area. Retrieved March 10, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20101219081010/http://hknanyc.org

24. Pløger, J. (2001). Millennium Urbanism – Discursive Planning. European Urban and Regional Studies, 8(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977640100800106

25. Regional Plan Association (2004, July). Fulfilling the Promise of Manhattan’s Far West Side. RPA. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from https://rpa.org/work.

26. Hell’s Kitchen Neighborhood Association (2004, November). HKNA’s Plan for the Hell’s Kitchen / Hudson Yards Area. Retrieved March 10, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20101219081010/http://hknanyc.org

27. Moss, M. (2011, November 1). How New York City Won the Olympics. Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management. New York University.

28. Conard, M., and Smiley, D. (2002). pg. 113.

29. Hell’s Kitchen South Coalition (2019, May 31). Hell’s Kitchen South Coalition Neighborhood Plan. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://cbmanhattan.cityofnewyork.us/cb4/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2020/04/hksc_neighborhood_plan_20190531-compressed.pdf